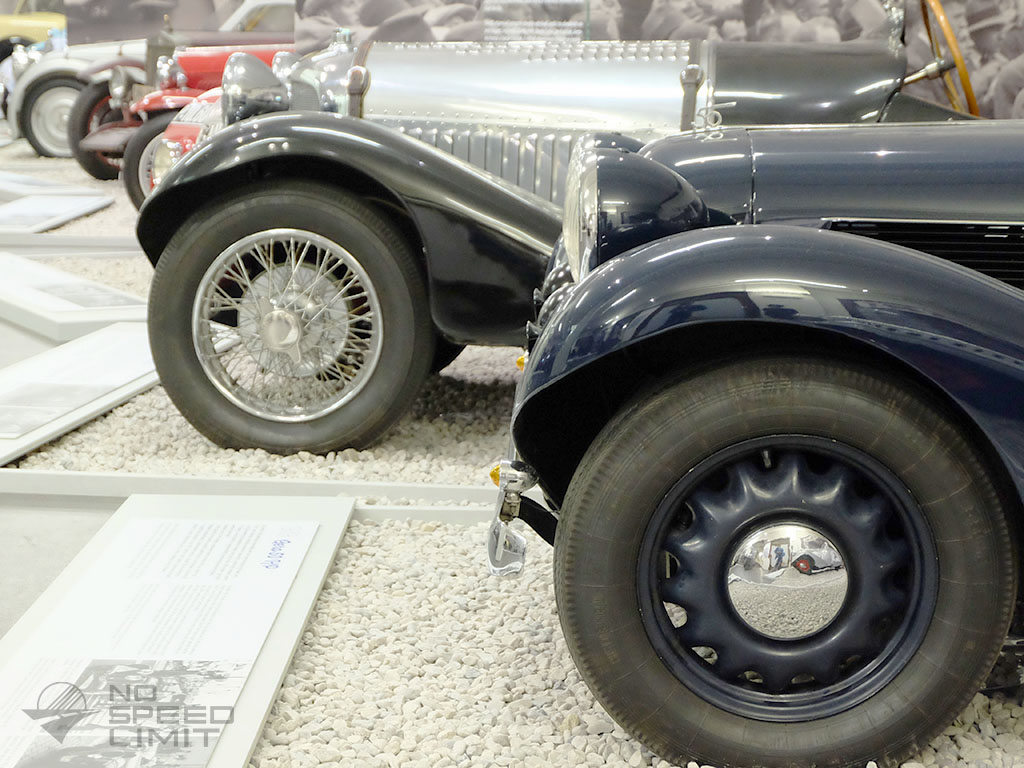

Škoda Museum

Prague, January 2022

The exhibition presents the history of interwar Czechoslovak motor sport and show its significance in the life of Czechoslovak society. A total of twenty-four cars with an interwar sports history are exhibited in an attractive installation evoking the period environment. Seven cars are from the collection of the National Technical Museum, two are borrowed from the collection of the ŠKODA Museum in Mladá Boleslav and the rest come from private collections. The cars at the exhibition are complemented by more than seventy sports memorabilia. These are mainly prizes and trophies from domestic and foreign car races and competitions, including sculptures by Ladislav Šaloun and Otakar Švec.

The three greatest legendary events of Czechoslovak interwar motor sport are detailed in the exhibition: the Zbraslav-Jíloviště hillclimb; the Grand Prix on the Masaryk Circuit and the 1000 Miglia of Czechoslovakia race. The exhibition deals also with other domestic car races as well as races of Czechoslovak drivers abroad and the long-distance car expeditions across foreign continents and also pays attention to the most important Czechoslovak car racers - the "fastest family of Czechoslovakia", i.e. Eliškaand Vincenc Junkov; Jiří Kristian Lobkowicz; Zdeněk Pohl; Jan Kubíček; Jindřich Knapp and many others.

.jpg)

After the end of the First World War, economic situation in the newly created Czechoslovak Republic was grim. The economic and financial system had been severely disrupted by the war. In the first post-war years, almost everything was in short supply and the rationing system introduced during the war, remained in place until 1921. Operation of motor vehicles, too, was subjected to severe limitations. Improvements came slowly. sale of gasoline was liberalised in January 1921 and only in March 1921 did the government lift the ban on operation of private cars. In a country impoverished by war, society tended to view cars as a decadent, asocial luxury that deserved to be highly taxed. Under such circumstances, interest in automobiles was minimal. Rather than a practical means of transport, cars were a costly hobby for a limited circle of the most fervent enthusiasts. As of mid-1921, there were in the territory of the Czecho- słovak Republic with a population of over 13 million just 4,332 passenger cars and lorries, meaning one car per 3,138 inhabitants. In motorisation, Czechoslovakia ranked fourteenth among the states of Europe.

Popularisation of cars could be helped by motorsport. The first two car races were organised already in September 1920. The first race followed the route of Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad) - Mariánské Lázně (Marienbad) - Cheb - Karlovy Vary. The second race went from Jíloviště to Řídká, but was open only for motorcycles, three-wheeled cars, and the smallest cars, then known as cyclecars. In 1921, the Carlsbad race between West Bohemian towns was joined by two important hill-climb races (Zbraslav - Jíloviště and Ecce Homo) and one automobile competition.

The most important motorsport event of early 1920s was the Czechoslovak International Reliability Trial, organised in 1921, 1922, and 1923. In this event, competitors drove in five or six competition days around the but entire Czechoslovak Republic, whereby in the east, they visited some places where many people never saw a motor car before. Criteria of evaluation of this almost 2,500 km long event were strict. Cars had to observe prescribed average speeds and their crews were not allowed to accept any outside help during the race. The competition also involved special tests. for instance, one of the day-long stretches had to be driven without switching off the engine. The fact that aside from various tire problems the most frequent malfunctions were broken leaf springs in the undercarriage attests to both the demanding design of the competition and poor quality of roads of that time.

.jpg)

In the 1920s, the most important events in Czechoslovak motorsport took place on the tracks of hill-climb races. To prepare a route several kilometres long and organise a race where participants start one after another, thus not overtaking each other along the way, had its advantages for both the organisers and the participants. A short race spared the drivers' cars and lowered the demands on organisers' effort and costs. Moreover, it apparently did not diminish the sporting experience and attractiveness for view- ers, because hill-climb races gradually became highly popular and their number in the sporting calen- dars was grew fast in the following years.

Most famous of these events was the Zbraslav-Jíloviště hill-climb, which always took place in the spring. It was founded already before the First World War, renewed in 1921, and with the exception of 1928 took place every year until 1931. It even achieved a degree of international fame in later years, it was includ- ed in the European championship and some of the best known European drivers competed and won there. The race was won three times by Otto Salzer, twice by Hans Stuck, and its other winners include Albert Divo, Rudolf Caracciola, and Eliška Junková. The fastest driver on this track was Caracciola, who in 1931 completed the 5.6 km long route in under 2 minutes and 43 second at average speed of almost 124 km/h. Alongside the absolute winner, who achieved the best time on the day, there were also other cate- gories, so there were always several laurels and several cups.

Another famous hill-climb race was the Ecce Homo, which took place near Šternberk for the first time in autumn 1921. In 1923, the sporting calendar expanded with the addition of Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad) hill-climb, Schöber hill-climb near Rumburk, and the Lochotín-Třemošná hill-climb. In 1924, racing cars for the first time competed in Brno-Soběšice, Dubí-Cínovec, and Knovíz-Olšany hill-climb races and in the years that followed, races were organised for instance also in Prague from Smíchov to Strahov, in Olomouc to Sv. Kopeček, to the Křivoklát Castle, from Pšovka to Mělník, or to Barrandov in the outskirts of Prague. In late 1920s and early 1930s, the golden years of hill-climb racing were coming to an end. In 1933, 1936, and 1937 the Ecce Homo still took place and in 1935, there was a race in Prague Jenerálka, but the core of domestic car races steadily moved to the racing circuits.

.jpg)

The racing career of Vincenc 'Čeněk' Junek and Eliška Junková, a husband and wife, forms a remarkable chapter in the history of Czechoslovak motor racing between the two world wars. A young Prague bank- er and his wife were both clearly talented drivers and most fortunately also had the means to participate in this extraordinarily costly sport as amateurs. They drove Bugatti cars and must have been treated in the Molsheim factory as highly valued customers. In 1922 to 1928, they bought here a total of eight racing cars

Čeněk Junek raced since 1922. Eliška raced for the first time in September 1924 in the Lochotín-Třemošná race. Equipped with the best and fastest cars they were winning most national races. In 1922-1928, Čeněk took part in 31 Czechoslovak races and took 10 prizes for first place in a category and 16 prizes for overall victory Eliška won in 1924-1928 in 19 national races a total of 13 first prizes in category and 3 overall victories. In many instances, they in effe t ra ed against each other, which is why they often competed in different categories. This was helped by the standard practice at the time, which made it possible to trans- form a sports car into a racing car by simply removing mudguards and lights, and to turn a race car into a sports car by installing mudguards and lights.

Since 1926, Eliška Junková successfully competed also internationally. She clearly demonstrated her ex- traordinary abilities in July 1927 at the German Grand Prix for sports cars at Nürburgring by winning in the category of 1.5 to 3-litre cars and the in May 1928 in the immensely difficult Targa Florio race in Sicily. In a strong field of the best European drivers, she for a long time led the race and then ended in excellent fifth place.

The story of Juneks did not have a happy end. On 15 July 1928, Čeněk suffered a fatal accident during his first international start at the German Grand Prix at Nürburgring. After this, Eliška never raced again.

.jpg)

The most important international car race of interwar Czechoslovakia was the Grand Prix at Masaryk circuit in Brno, which was in 1930-1935 and then again in 1937 organised by the Czechoslovak Automobile Club for Moravia and Silesia. It always took place in September and was regularly attended by the best European drivers with the most powerful racing cars. Its quality is attested also by the names of its winners, which include von Morgen and Leiningen with their Bugatti in 1930, Chiron in a Bugatti and Alfa Romeo in 1931-1933, von Stuck and Rosemeyer with their Auto-Union cars in 1934 and 1935, and Caracciola with a Mercedes Benz in 1937. In 1936, the race did not take place due to a collision of dates in the international sporting calendar and in September 1938, Czechoslovakia already had completely different things to worry about.

The Grand Prix at Masaryk circuit was open for racing cars in two categories. The bottom group included cars with engine capacity of up to 1.5 litres, whereas the top category included those with a higher engine capacity limited only by general conditions placed upon cars entering any Grand Prix. Until 1935, both groups raced at the same time, in 1935 they had a joint start, whereas in previous years, the bottom category started a few minutes after the top one. In 1937, cars in the bottom category raced in a separate shorter race, the Brno Grand Prix. Cars over 1500 cc went through the 29 kilometres long circuit, which took them on regular roads, seventeen times and winners were achieving average speeds which over time increased from 101 km/h to 138 km/h. Czechoslovak racing drivers always competed in the Masaryk Grand Prix, both with foreign or Czechoslovak-made cars. It was not, however, easy for them to succeed among the best international drivers. In the top group, the best result by a Czechoslovak driver was the fourth place, which was achieved by Jan Kubíček in 1930 and Jiří Kristian Lobkowicz in 1931. In the bottom group, Czechoslovaks Florian Schmidt and Bruno Sojka several times scored the second or third place and in 1931, Schmidt even won the race. They all drove Bugattis.

The route was always lined with spectators. in some years, there were up to 200,000 of them. Domestic press, too, covered this racing event extensively. But it was not only a top sports show organisation of such an important international racing event offered Czechoslovak citizens a sense of internationality and growing importance of their new state.

.jpg)

During the interwar era, Czechoslovak drivers also took part in car races and competitions abroad. They achieved several remarkable successes, but none managed to join the élite group of best European drivers, Perhaps the closest to that came Eliska Junková, whose fame was significantly boosted by the fact that she was a woman.

In 1924-1925, small two-cylinder Tatras, both standard and racing models, achieved several international successes. They won their most famous victory in 1925 in the Targa Florio race, when drivers Sponar and Hückel ended with them first and second in the category of up to 1.1 litres.

During several years that followed, Czechoslovak colours were defended abroad mainly by Eliška Junková but she was not alone. When in July 1927 she won in the German Grand Prix for sports ars at Nürburgring in the 1.5 to 3-litre category, she was in the list of winners Joined by Prague driver Hugo Urban-Emmerich, who with his Talbot won the category of 1.5 litre cars. In March 1926, Edgar Morawitz, another driver from Prague, ended with his Bugatti 39 at the Rome Grand Prix second in the category of 1.5-litre cars.

Still, Czechoslovak drivers took part in international races of the Grand Prix category only occasionally. For the most part, they.competed in shorter and less Important races in Austria, Germany, and Poland and their successes were not numerous. Among those who brough trophies home in the 1930s, we should mention Jan Kubiček, Jiri Kristian Lobkowicz, Zdeněk Pohl, Florian Schmidt, and Bruno Sojka. They all competed with Bugatti cars.

At this time, Czechostovak drivers with regular touring cars of domestic production successfully competed in many international events ranging from rallies to car salons, through various drives of reliability and regularity and all the way to highly demanding and prestigious competitions such as the Alpine rallies, Rally Monte Carlo, Rajd Polski, or the 10.000 km Fahrt of the German Auto Club.

.jpg)

In the 1920s and 1930s, most car owners were just like today more interested in the number of seats, size of the trunk, and fuel requirements of their vehicles than in their maximum speed. Even in interwar Czechoslovakia, however, there were drivers who clearly preferred a sporting character of their cars to their basic utilitarian properties. Most never took part in any race or competition but even so, they bought and drove cars which may have been very impractical and uncomfortable, one could not fit a family in them, but their drivers enjoyed the thrill of a fast ride. Such car owners were, naturally, few and far between.

Dynamic properties of a car are determined first of all by output of the engine but of crucial importance is also car's weight. The ideal combination is an extraordinarily powerful engine and a light construction with a simple, usually just two-seat body. But this is a costly design which is also why few of the most powerful sporting cars made by the best international manufacturers were sold in interwar Czechoslovakia. Already in the 1920s, however, it became fully apparent that a satisfactory and significantly less costly solution can be found in light two-seat sports cars with small and not very powerful engines. Good dynamic qualities of such cars were driven mainly by their low weight. Such cars were accessible to a much broader range of potential clients, but Czechoslovak car manufacturers did not make any at this time numerous such cars were thus created individually, either by custom-building or by rebuilding an existing car. Most were, however, imported from abroad. In most cases, these were small French sports cars such as Amilcar, Salmson, Sénéchal, Rally, and SCAP.

In the 1930s, the situation had changed. Czechoslovak car manufacturers started to pay more attention to customers interested in sports cars and offered especially their smaller and cheaper types also in two-seat sport versions. These were not genuine sports cars but they were more versatile, offered more comfort, and most customers were happy with them. Once they appeared in the market, the number of imported sports cars declined.

.jpg)

Even in early 1920s, driving a car from Prague to Paris was an adventure that deserved a separate article in the press. Ten years later, travelling through Europe by car was relatively commonplace and Czechoslovak explorers undertook with their Czechoslovak-made cars even rather demanding expeditions around other continents. Although such journeys were usually undertaken for purposes of promotion, exploration, or research in ethnography or natural sciences, they all required considerable sporting a hievements on the part of their participants.

In 1931, the sculptor František Vladimır Foit and zoologist Jiří Baum travelled in their small two-cylinder Tatra 12 through the entire African continent from north to south. Four years later, Baum with his wife Růžena traversed in their three-axle Tatra 72 Australia, Japan, and part of the United States. Small Aero cars became famous especially thanks to two journeys through northern Africa. In 1933, the Aero-Spexor expedition included three Aero 18 HP cars. In the following year, they were followed by a Blue Team Aero consisting of four Aeros 20 HP. Three of those cars had a fully female crew. The traveller and writer František A. Elstner participated in both of these north African expeditions.

Expeditions on other continents in the 1930s were well-served also by the small Škoda Popular and Škoda Rapid cars. In 1934, seven young men drove their four Populars from Prague to India. Elstner and his wife also used Škoda Populars for their journeys. With one, they drove in 1936 over one hundred days some 25,000 km through the United States and Mexico, and with another one, they travelled through Bolivia and Argentina two years later in 1936, Břetislav J. Procházka drove with his Škoda Rapid around the globe in 97 days, while Marie and Stanislav Škulina took their Rapid in 1936-1938 twice through the whole of Africa, once from west to east and once from the south to the north. At a time before television and before high-capacity passenger planes, opportunities for visiting distant exotic lands were limited long distance travelling by car thus naturally attracted a lot of public attention. Upon return, travellers were usually welcomed by crowds of fans and admirers who were looking forward to their photographs, films, articles, books, and lectures.

.jpg)

Top events in car racing in Czechoslovakla in the 1930s were the six Grand Prix on the Masaryk circuit, three Czechoslovak 1000 Mile races, and the Zbraslav-Jlloviště hill-climb in 1930 and 1931. Other races were of a more local Importance and were attended only by Czechoslovak drivers.

Hill-climb races, which dominated the domestic sporting calendars in the 1920s, were in the following decade replaced by competitions on racing circuits. These were classical road circuits on public roads, which were for the duration of the race closed to the general public. They varied in length from just several kilometres to several dozen kilometres and drivers had to pass them during the race several times.

In terms of length, the only race that could be compared to a Grand Prix was the 500 Slovak Kilometres in 1937 and 1938. It took place on a 100 kilometre circuit of Bratislava-Malacky-Baba-Pezinok-Bratislava, which drivers had to take five times. Other races were much shorter, usually between 40 to 150 kilometres long, with only a few longer ones.

Some races, for instance the July 1933 race through streets of Hradec Králové, which proved to be very popular with the public, took place only once. Most, however, took place several times in conse utive years. Plisen had its Lochotin circult, Zlin its Zlín circuit and later its Zlin Eight, Stará Paka had a Krakonoš circuit, and Ceský Brod, Bohdaneč, Zdiby, Brandýs nad Orlicí, or ždirec nad Doubravou also had their circuits. The routes of these races were always lined with thousands of people and the full programme took several hours, This is because cars were divided in several categories and quite often, each category had its own race, In some cases, only a handful of cars entered the race, so to achieve a good result, all they had to do was to complete the race.

Top categories were often won by drivers who drove Bugatti racing cars. The most successful of these drivers were Zdenek Pohl, Bruno Sojka, Jan Kubicek, Antonin Komár, and Väclav Vanicek. In the lesser categories, cars of domestic production also fared well, especially the Aero 18HP, Aero 20HP Aero 30HP, Z-4, Walter Junior 55, and Jawa 750. In some cases, they were not sporting specials but regular serially produced touring cars with engines tuned to a higher output.

.jpg)

In summer 1932 the Crechostovak traffic rule which set maximum speed of motor vehicles at 45 km/h was lifted. From then, speed was restricted only in villages and towns, where a new limit was set at 35 km/h. Outside built-up areas, the speed of cars and motoreycles was not limited.

This legislative change led to the birth of a legend of Czechoslovak interwar motorsport, the Czechoslovak 1000 Mile automobile race, which was organised by Autoclub of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1933, 1934, and 1935.

This was a speed race open to regular touring cars, which took the route of Prague-Kolin-Německý Brod-Jihlava-Velké Meziřici-Brno-Břeclav-Bratislava, whereby participants went from Prague to Bratislava and back withhout any break for rest twice. All in all, it was thus 1600 km of straight driving. Participants drove on open roads, that is roads that were not closed to other cars, and the only criterion taken into account was the total time at finishing line. Stops along the road, such as those necessitated by changing a flat tire, refuelling, or at railroad crossings were not deducted from the driving time. The cars were evalueted in five categories based en engine volume then there as an overall ranking and teems of three cars could compete for a prestigious team prize donated by President of the Republic. Most prized, however, was overall victory, that is, finishing in the shortest time. The fastest time was achieved by Jindřich Knapp in a Walter Standard S sports car with a six-eylinder 3.2 litre engine. He finished the race in 1934 in 15 hours 22 minutes and 37 seconds, achieving an average speed of 103.6 km/h.

All three years of this event enjoyed extraordinary interest of the public. Its route wes lined with hundreds of thousands of people; betting offices accepted bets on winners and in a raffle, one could win a car or weekend cottage. Domestic press paid a lot of attention to the competition and since 1934, its progress was alse broadcast live from the Autoclub building by nationwide radio. The Czechoslovak 1000 Mile was thus not only a remarkable sporting event of its time but also an important social occasion.

.jpg)

Unlike races, where ranking is decided solely on the basis of time at the finish line, car competitions took into account other things than only the car's speed. Participants had to maintain prescribed average speeds and usually also pass special speed tests, but the main goal was always to test cars' reliability and abilities of their crews. What always mattered was the regularity of driving, sometimes also good orientation in maps, low fuel consumption, the art of overcoming the challenges of winter terrain or driving at night, eventually success in various tests of driving ability. Some competitions were opened only to ladies, others had the nature of rallies or racing to a particular place, and some took drivers even across borders.

While success in racing usually required expensive sports or racing cars, in competitions one could win with ordinary touring cars. This natural expanded the number of possible participants and even domes- tic manufacturers were often eminently interested in participation. They viewed it as an opportunity to demonstrate the reliability and good qualities of their serially produced passenger cars. From the mid-1920s until the end of 1930s, dozens such competitions took place in Czechoslovakia on na- tional or club level, but none achieved any special renown.

Perhaps the most important national car competition of the 1930s took place in September 1937 and it was in fact rather international. While it led through the whole of Czechoslovakia, from Prague to Brno, Bratislava, Košice, and Užhorod and all the way to the border with Romania, from there it continued to Bucharest and ended in Yugoslavian Beograd. This competition, open to both cars and motorcycles, was called Through the Little Entente- a hint to the political and military alliance of Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. In the worsening political atmosphere of the second half of the 1930s, it was supposed to demonstrate this alliance, as attested by the fact that armies of all three states sent their teams and their crews competed in uniforms.

No one however, was dissuaded by this demonstration and just a year later, in September 1938, Czechoslovakia was stripped off its borderlands by the Munich Dictate, and in September 1939, the Second World War broke out. By that time neither interwar Czechoslovakia nor its motorsport were in existence.

Škoda Museum

The phenomenon of Jawa

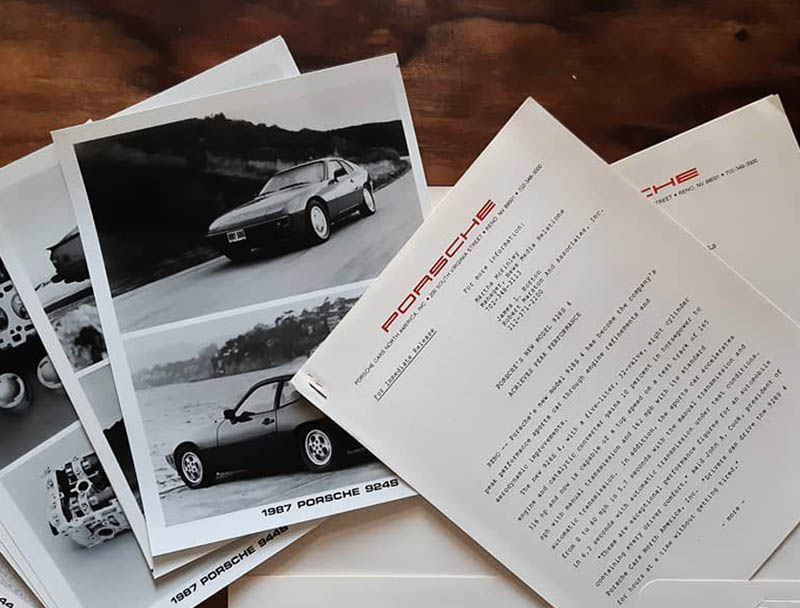

Porsche Press kit

Porsche Literature

Our Porsche Cars