Porsche 911 - Engine Development

The water-cooled six-cylinder power units of the Boxster and the new 911 set the standard in modern sports car engine technology.

„Our pledge to the six-cylinder boxer engine is more than just tradition“, states Horst Marchart, Porsche’s Member of the Board for Technical Development and the Managing Director of the Weissach Research and Development Centre. „Considering the sum total of its properties, the boxer engine is the ideal configuration for a six-cylinder sports car of the type we build.“

Very low in design, the boxer engine is the ideal match for Porsche’s two automobile concepts, the mid-engined Boxster and the rear-engined 911. With the pistons running in opposite directions, smoothness and refinement are enhanced to perfection. A six-cylinder horizontally-opposed power unit is entirely free of mass forces and mass momentum, the crankdrive is perfectly balanced. And this ensures not only top quality and behaviour in mechanical terms, but also allows a sports engine of this calibre to reach high engine speeds without the slightest problem.

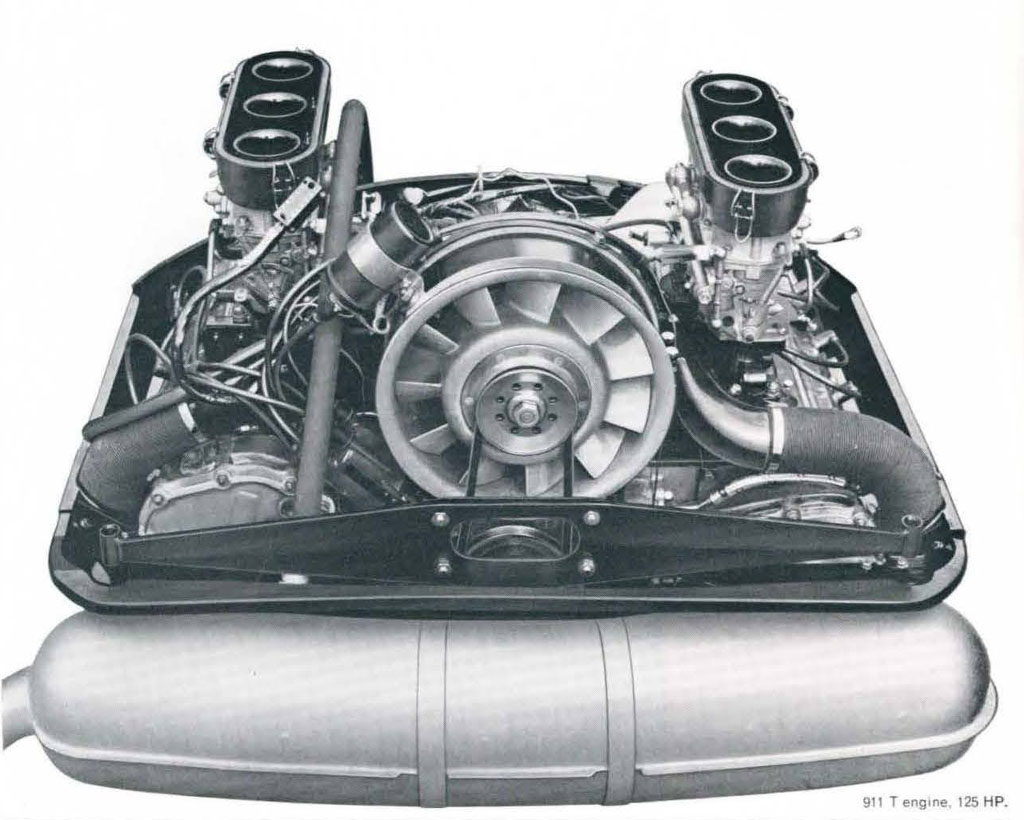

The changeover from air to water cooling was necessary in technical terms in order to master all the requirements of four-valve technology. Four valves per cylinder are indeed essential these days in order to combine superior power and performance with equally superior fuel economy and emission control.

Porsche’s clear pledge to water cooling is also based on many years of practical experience. And this means not only the good features and qualities offered by Porsche’s water-cooled production engines with both four and 8 cylinders. The TAG engine enabling McLaren to win the World Formula 1 Championship three times, for example, was a water-cooled V6 designed by Porsche. In GT racing, in turn, Porsche has been building water-cooled six-cylinder boxer engines ever since 1977, initiating an exemplary series of successes in motor racing that has continued throughout these 20 years to this very day. Engines of this kind are to be found in Porsche’s Le Mans-winning cars and in the very latest 1998 911 GT1 which scored a one-two victory in this year’s 24 Hours of Le Mans, marking Porsche’s 16th triumph in this world-famous race.

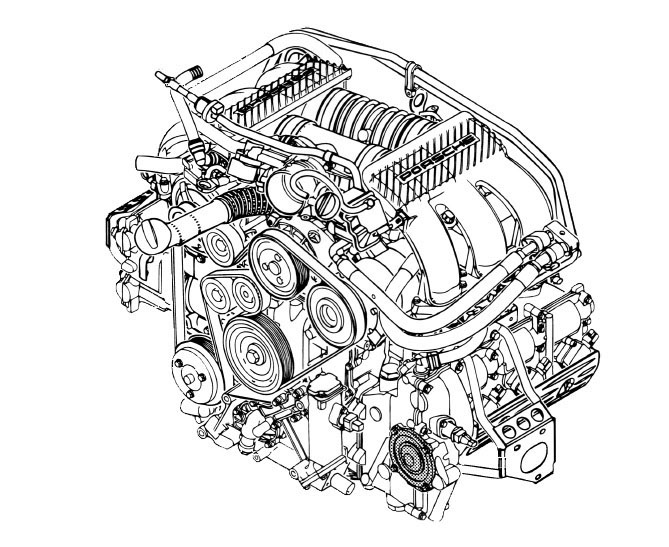

The engine of the Carrera naturally differs significantly from these racing machines, reflecting Porsche’s new principle of using shared parts: In their fundamental design and configuration, the power units of the Boxster and Carrera are basically identical. But in terms of size and output these two six-cylinders are clearly different, the Boxster displacing 2.5 litres and developing maximum output of 204 bhp (150 kW), while the 911 Carrera displaces 3.4 litres and develops maximum power of 300 bhp (221 kW).

Through their configuration and the materials used, Porsche’s new boxer engines stand out clearly as ultra-modern power units built for all the requirements of today and tomorrow. The two-piece crankcase separated down the middle is made of pressure-cast light-alloy. Offering very good surface quality, this material ensures perfect production of even very delicate parts and components, at the same time keeping the crankcase very light. And since this kind of pressure-casting is not suitable for the cylinders and their liners subject to the most demanding running conditions, the six cylinder liners are made of silicon alloy subsequently cast into the crankcase during the production process.

A further speciality of the Porsche engine is the separate bearing bridge accommodating the crankshaft with its 7 main bearings as well as a layshaft. The aluminium block encompassing the central section of the crankdrive incorporates cast-steel support elements to give the bearings a strong and secure fit. On the Carrera engine revving up to a maximum speed of 7300 rpm, this component is reinforced to a far higher standard than on the Boxster engine where the speed limiter cuts in at 6700 rpm.

Featuring a large bore and short stroke, both engines are sporting and dynamic in their configuration, ensuring both superior refinement and the ability to run smoothly and reliably even at very high speeds. Bore on the engine of the Carrera 4 is 96 mm or 3.78“, stroke measures 78 mm or 3.07“.

The boxer engines of the Porsche Carrera models also differ from traditional design concepts in terms of their oil circuit. Taking up approximately 12 litres of oil, the „classic“ dry sump lubrication on the engine of the 911 required a separate oil tank connected by pipes to the engine itself. Now the integrated dry sump lubrication keeps its oil reserve of approximately 10 litres in a chamber within the engine housing separated from the crankshaft area.

The next example of technical progress offered by the boxer engine is its cylinder heads: Each of the two cylinder heads houses two camshafts operating two inlet and two outlet valves per cylinder. This increase in the number of valves from two to four offers three advantages in particular:

The drive concept for the four camshafts introduced by Porsche adds yet another outstanding example to the Company’s high standard of engine construction: From the crankshaft power first flows through a chain to the layshaft already mentioned. Featuring one pinion each at the front and rear end, the layshaft then drives two further chains leading to the outlet crankshafts. This displaced geometry saves space by using the displaced rows of cylinders left and right in order to accommodate the two chain boxes. It is indeed this particular design which, to a large extent, makes the water-cooled boxer 70 mm or 2.76“ shorter than the air-cooled version on the previous model, even with the distance between cylinders remaining the same.

Featuring two camshafts and one camshaft adjuster, the current six-cylinder is able to vary intake valve timing by 25°. This is done via a hydraulic camshaft adjuster on the chain between the outlet and intake camshafts, this process of intervening in valve timing offering several advantages:

Whenever Porsche’s engineers replace air cooling by water cooling, the new water cooling system must be a very good one. So to „refresh“ the cylinders and combustion chambers they have chosen a principle otherwise to be found on racing engines: The flow of coolant is clearly separated on each side by the cylinder gasket. With the ducts being appropriately designed, this allows the temperature of the coolant to be adjusted perfectly to current requirements. The flow of coolant through the cylinder heads and along the cylinders themselves is not lengthwise, as is otherwise the case with production engines, but rather crosswise from the outlet to the intake side, again reflecting a technology well known from motor racing. Coolant then flows back through two separate longitudinal ducts, the big advantage of this system being that the cylinder heads and the cylinders themselves always receive the same, sufficient and consistent supply of coolant.

Water cooling ensures a good thermal balance also elsewhere, both the coolant itself and the engine oil flowing through a heat exchanger. With the coolant reaching its operating temperature relatively quickly, it is able to initially warm up the engine oil almost immediately after the engine has started. And then, with the oil becoming hotter than the coolant after some hard driving, the temperature balance works the opposite way, the coolant serving to cool down the oil. The same principle is incidentally also used to cool the automatic transmission fluid on models fitted with Tiptronic, in which case the 911 comes with three water coolers at the front.

Made largely of extra-light fibre-reinforced plastic, the intake system, thanks to its good flow dynamics, its carefully matched ducts and their smooth surface, makes a significant contribution to the superior output and powerful torque of the two boxer engines. The six intake manifolds leading to the intake valves join to form units of three on the other side leading into an air collector. A special feature to be found here on the engine of the 911 is the butterfly between these two resonance chambers opening at 2720 rpm and closing again at 5120 rpm. Thanks to this solution the cylinder charge, torque and engine power are all optimised in one and the same process.

On the other side of the engine emissions flow through a stainless-steel emission system with two metal-based catalytic converters for thorough and efficient emission management.

A computer serves to mastermind the flow of sparks within the engine, with no less than 300 sparks per second whenever the six-cylinder is running at 6000 revolutions per minute. Thanks to anti-knock control the computer is able to determine the right ignition timing even when running on low-grade fuel with a quality level worse than premium plus. And the injection system with electronic management operates as reliably as ever, delivering 300 or more exactly metered bursts of fuel per second to the intake valves at exactly the right time.

Innovative technology of this calibre gives the water-cooled boxer engine of the Porsche 911 superior output of 300 bhp (221 kW) at 6800 rpm. Maximum torque, in turn, is 350 Newton metres or 258 lb-ft at 4600 rpm. But even this kind of progress, as clearly as it is described by these figures alone, cannot match the experience of actually driving the car.

The water-cooled flat-six power unit in the Porsche 911 really reveals its true qualities when required to run at high engine speeds, where it combines supreme torque with almost unlimited free-revving performance up to 7000 rpm and more. The sound accompanying this new fortissimo of speed and performance naturally remains within the limits prescribed by law, but just as naturally retains that typical Porsche quality. So this certainly is the Porsche six-cylinder boxer with that throaty chortle so typical of the marque.

Porsche 911 - Engine Development

.jpg)

Porsche Formula 1 engine TAG Turbo PO1

Porsche Press kit

Porsche Literature

Our Porsche Cars